The Problems with Purgatory ~ Part Two

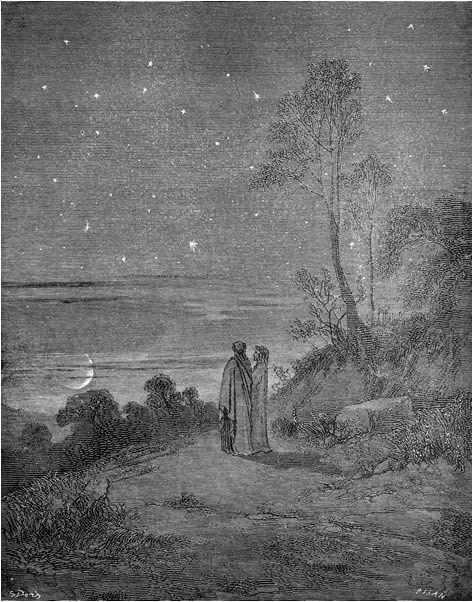

Designed as a mountain, Dante’s Purgatory does everything that it should as we take the next step on the soul’s journey. It tells us that redemption is possible, although it takes some work; it shows us that our salvation is reliant upon our willingness to accept personal responsibility; and, it stresses that mistakes—even serious mistakes—are part of the human experience. More, it tells us that we are not exempt from trying to resolve conflict, ameliorate our moral faults, or ignore our duty to find just answers to sticky problems. In Dante’s Purgatory, we are not allowed to kick unpopular or complicated issues down the street; we have to face them. And, indeed, the mountaineers of Purgatory do just that, making the story a rewarding and dramatic experience for those of us who are observing their transformation. However, Purgatory—by definition—means that accountability is at the core of the story, and it is for this reason that I believe it is sometimes difficult for readers and artists to engage with the text.

Now, this isn’t to contend that Dante’s readership cannot accept responsibility, or that the creative visions of countless talented minds cannot comprehend the importance of owning our flaws before entering Heaven. What I mean is that Purgatory is a very different story than the one told in The Inferno, where hope is banished on its threshold, and all the souls swirl through horrifying penalties and ultimate oblivion. In other words, Hell is a place where change is not expected, and where conversion will not take place; whereas Purgatory tells the tale of ongoing, mature self-reflection coupled with a series of cleansing actions that promise to purify the spirit. Here, perfected change is the story, and rather than spinning down and into inglorious obscurity, Purgatory reels us upward, pulling us through similar discussions of sin, but toward a contrasting and happier end. Therefore, we cannot insist that Dante simply give us an alpine-like adaptation of The Inferno, especially when the stakes are different and the sinners are contrite.

It is for this reason that I find Purgatory a more interesting and satisfying adventure than The Inferno. Upon the terraces, moral culpability and consequence are openly discussed, and we discover that we are charged with handling our burdens with grace, dignity, and duty. This is meatier conversation, full of nuanced philosophical arguments, and sincerely given advice. There is no doubt that Purgatory’s ascent is difficult and sometimes unpleasant, but it does not tax us more than necessary. Further, it is a place where the soul makes a difference by making an effort, underlining the healing powers of forgiveness and justice, as opposed to the emptiness of treachery and revenge. More importantly, we find that “…as the load of sin is gradually lightened by penitence, the going becomes easier and easier, until on the last stair it is as though the pilgrim’s feet had wings” (70). Indeed! The physicality that Dante’s mountain demands ingeniously mirrors many of our own experiences with accepting responsibility for our actions: do we not initially feel the weight of our responsibility? Isn’t the burden heavy? And, yet, isn’t responsibility just as often liberating, as it allows us to have some say in our destiny through the acknowledgment of our limitations and weaknesses? Quite so, I say! Hence, I urge anyone who is interested to look up the slope of Mount Purgatory, and refuse to let its steep angles and rocky terrain dampen your spirit. I assure you, the view is magnificent!

___________________________

Alighieri, Dante. Purgatory. Trans. Dorothy L. Sayers. London: Penguin Books, 1955. Print.